They are lean men, born in Africa and now in the last decade of their lives. Leathery, freckled skin folds over elbows and knees, their hair is mousy, white, dirty blond, usually worn long. They drive a motorbike from the 1940s, or a 40-year-old Land Cruiser, or maybe even an ancient Ford. They live at the simplest possible level – sometimes so poor that running water and electricity are real luxuries, forced to tinker endlessly with their broken down water pump, with greasy generators or with the dusty, rusty wires of their car engine, everything disassembling in parallel to their own bodily decay. The roof of their house leaks, in the evenings they read the discarded paper from yesterday accompanied by the solemn tik-tak of drips collecting in a metal sufuria. The curtains are mere shredded rags at their windows. The scant furniture is colonial issue brown wood from the 1950s -solid, ugly, functional. Sometimes animal skulls leer from the walls, or African artifacts crumble in a hand-carved bowl. A mask, a carving of an elephant, an antique beaded Turkana doll, a moldy leather chest containing – who knows what? The last love letters, the kitchen toto, photographs of the family farmstead 50 years ago, of a lost child.

Perhaps they are well off and own a magnificent old stone house in the upper class white areas of town – Muthaiga, Karen, Kitisuru, or “up-country” in Nanyuki or Eldoret. Spacious buildings with fireplaces, many rooms, carvings, masks, zebra skin rugs and leather chairs and an extensive library of tomes on African history or long-lost tribal rituals. They are not disturbed by current politics, nor are they involved. Their servants have been with them for decades, faithful and ever-smiling cooks, gardeners and maids. The co-dependency was established 60 years ago and there is no reason to change it. Who will die first is the secret question whispering in the folds of the heavy drapes.

Perhaps they are foreigners – French, German, American, Polish – who arrived in Africa as young students or volunteers or even refugees and have contracted le mal d’Afrique – that insidious disease that infects so many people who have tasted the raw red dust of the highlands on a gritty tongue or become enamored of the indigenous ways of life and find in them some soul echo that resonates in their deepest being forever. They have renounced their homeland, forgotten their roots and found their path in the cluttered city or its outskirts, or in the last remaining areas of bush, committed to performing the good works that ought to make life better for the African but serve also to alienate him ever more from his own roots.

There are the women, too. War correspondents who have traveled the length and breadth of Africa, found their dark lovers here, adopted African children. Animal lovers who have devoted their lives to the r escue of one or other species, whose homestead features tame ostrich, giraffe or hyena. The women who came with their men, lost their men, maybe their sons as well, and stayed, hardened, saved by their gardens, saved by their cook, saved by the country club and the chocolate desert, immune to the ravages of their sun-drenched skin.

escue of one or other species, whose homestead features tame ostrich, giraffe or hyena. The women who came with their men, lost their men, maybe their sons as well, and stayed, hardened, saved by their gardens, saved by their cook, saved by the country club and the chocolate desert, immune to the ravages of their sun-drenched skin.

There are those, like me, compelled to document this Africa that shakes us at the end of a mighty pole, like the fluffy yellow mimosa, subject to the winds of time. We write books, make films, take photographs, publish academic tracts, speak Swahili poorly, sell our work elsewhere, endlessly fascinated, debating, questioning, worrying. We leave, we return, we have other homes, other loyalties, yet we cannot break free. We yearn to truly belong, we envy those who do, yet we enjoy the air of romantic exoticism and wonder expressed abroad when we say, “I am a White African.”

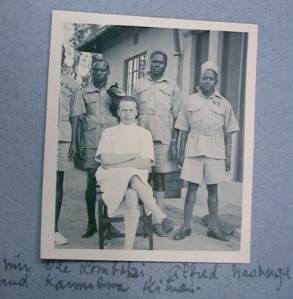

There are the young ones, third or fourth generation, born of British farmer or South African Boer families. At home in the wild, consummate lovers of nature, of wildlife, of the early morning dew on the starling’s wing and of the rusty smell of earth before the rains. They may hunt as well as they start a new dot.com business. They may organize a music festival as well as they run a farm. They are ignorant of racial divides and move within a totally integrated circle of African, Asian and European friends. Theirs is an uncertain future, for they have recognized corruption as the great enemy of the nation that does not spare even the fourth generation White African. Could their land be confiscated? Will they – or even their parents – ever get citizenship? A legitimate work permit?A resident’s permit? How many times can a person who has lived in Kenya for 50 years, is married to a Kikuyu lady and supports three charitable foundations travel over to Tanzania and back just to get a “tourist” visa? And what is the end result of the frustration felt by White Africans who support whole families of African employees, pay school and medical fees, behave as good citizens, even though they aren’t, and generally act as full-fledged, contributing citizens of this nation, even though they are not? Will reverse racism force them to take drastic measures to preserve what they have inherited or built? Will the New Kenya – this vibrant, explosive, truly African nation, accept the new breed of White African as an integrated part of society? Or will they be forever dreamers, spending a lifetime merely passing through on the way to somewhere else, nostalgic for the unspoiled lands of their grandfathers, for the crackling photo albums of bygone days, for the faded pictures of Colonial times shared on Facebook?

Defined as a person of European descent who is born and raised in Africa, the very designation “White African” may disappear altogether, for as time moves on and youth connects with the world through social media, there may truly no longer be the need for such divisive descriptions. May we come to a place where an African is an African, valid to the state of the nation no matter what color his skin may be or where his original birthright finds its roots? Is this a desirable condition for White Africans? Would we be as proud to call ourselves Africans as we are to call ourselves White Africans? What old ghosts might wave their flags in surrender? What new demons might make themselves visible in the corner of our eye? And if we are to call ourselves simply “Kenyans,” where is the validation that makes us so?

These are the questions we face if Africa is our true home, the place where our soul lives, the irreplaceable font of our dreams, our work and our daily encounters with the “other.” These are the questions that the Kenyan power structure must ask itself if “white” is indeed included in the “One Kenya, One People” rainbow that makes for such a facile slogan. Or is white, after all, the one invisible colour today, left out of the kaleidoscope vision for the nation’s future? After all, following the famed advertisement for Omo detergent – “Omo Washes Whiter!” – we used to joke that “Jomo Washes Whiter.” Could it be that we were entirely washed out? I say “No!” to that suggestion. It is up to White Africans ourselves to define our identity within Kenya, to be proud citizens even without citizenship and to share the nation’s future, whatever it may be. We may be the only drops of milk in the Kenyan coffee – but it’s damn good coffee!!

Iki, so well observed and even better written! As one of those white Kenyans, I can wholeheartedly support your observations and conclusions. I just love your writing and your films! Keep it up! Cheers from Nairobi.

Thanks so much, Christian, as always, for your support!